KA-BAR Wharnstalker

Tracing the origins of anything related to knives is difficult.

The sheer length of time knives have been used by humans makes going back to the first anything often impossible. Who made the first knife? Well, it depends on what you classify as a knife, but it was probably some unnamed Australopithecine dude more than two million years ago.

But when you have the ability to trace a single invention related to knives to a single moment, it’s always cool.

In a series of posts, I will be examining the history of specific innovations and evolutions in the knife community.

This first post will deal with the Wharncliffe blade. You can also check out our list of the top Wharncliffe Blades.

The Origins of the Wharncliffe

The year is 1820 (or thereabouts). For a look at what was going on in the world, Maine had recently become the 23rd state in the burgeoning United States of America.

According to the 1878 edition of “British Manufacturing Industries,” the first Lord of Wharncliffe — James Archibald Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie — was having dinner with his relative Archdeacon Corbett in Great Britain.

During wine, the conversation turned to cutlery and the lack of innovation in “spring knives,” which I assume meant slip joints. Here’s an excerpt:

Not wishing to criticise where they could not improve, they laid their heads together, and with the assistance of a practical man succeeded in producing a new pattern knife.

Lord Wharncliffe was the patron of Joseph Rodgers & Son — Cutlers to Their Majesties and one of the most important figures in the famed Sheffield cutlery industry — and so he presented the pattern to him.

The blade was created and called the Wharncliffe blade after the Lord himself a few years later.

(To say that the Wharncliffe first appeared in the 1820s may be a bit disingenuous.

Sometime before the 11th century, the Vikings had a fixed blade called the Seax or Sax that had a straight edge and a straight tapering toward a point. This looks like the present day interpretations of the Wharncliffe pioneered by Michael Janich as you’ll read later in this article.

But I still argue the origin point of the Wharncliffe blade is in the 1820s and 1830s.)

What is a Wharncliffe Blade?

Anecdotal evidence says that Lord Wharncliffe wanted a knife with a thick and strong blade. The result was the blade known as the Wharncliffe.

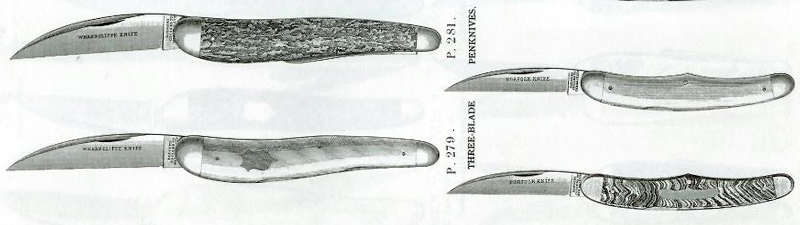

The original Wharncliffe blade had a rounded spine that tapered gradually toward a point and a straight full flat-ground edge. Like this (though maybe even thicker):

The standard definition has since broadened a bit to include any blade with a straight edge that tapers toward a point. (Although I’d argue some light curves in the blade don’t immediately disqualify it from being a Wharncliffe.)

The Wharncliffe is widely mixed up with the sheepsfoot blade and lesser known lambsfoot blade. In fact, manufacturers will often mislabel the blade style.

Whereas the Wharncliffe has a spine that gradually tapers to a point, the sheepsfoot blade has a spine and edge that remains parallel until the spine more dramatically curves to the edge. The result is lack of a piercing point.

The lambsfoot has a spine and edge that start gently tapering toward one another and has a point somewhere between a sheepsfoot and Wharncliffe. This one is rarer to see classified though.

For even more nitty gritty, there is a coping blade that is kind of like the reverse of a lambsfoot because it tapers outward. Some people debate on this one — whether it is a cut off pen blade or something else.

These are exaggerations of each to better see the difference, but if I am off base with these definitions, let me know in the comments.

Early Wharncliffe Uses and Models

Case Seahorse Whittler

From what I found, the original intent of the modern Wharncliffe blade was for woodworking. Those early models from Sheffield had really thick blades that could be used for everything from whittling to splitting wood.

There are advertisements from 1852 showcasing Rodgers Wharncliffe Whittlers, according to Rod Neep.

The pattern rose in popularity in the late 1800s and the knives were exported to America. Eventually the pattern was picked up by companies like Case. Someone more versed in the history of Case could likely tell you when the Wharncliffe was adopted in American knives, but Case did eventually adopt the blade design.

Other slip joint companies in the early days of America used the Wharncliffe pattern in whittlers as well.

From Woodworking to Tactical Applications

For the most part, the blade’s length, thickness, and design lends itself to whittling. And for decades, that was the primary purpose of the Wharncliffe.

But these days, you see the Wharncliffe making a comeback in a decidedly different category than whittling: the tactical and self-defense arena.

This can be traced back to one man: Michael Janich.

Michael Janich

Janich wrote a very detailed and fascinating piece in the Knives 2018, 38th Edition from Blade describing how the Wharncliffe went tactical (which I would say is almost like Dylan going electrical).

I won’t go into great detail because you should absolutely read his piece, but Janich was interested in knife fighting and combat knives growing up. When he made his first knife, it reflected his original belief that a fighting knife should be a Bowie-like knife with a curved blade.

But when Sal Glesser reached out to Janich — the pioneer of Martial Blade Concepts — about making a knife under Spyderco in 1997, he reconsidered his approach because most fighting knives cut poorly. After some experiments, he found Frank Centofante’s Wharncliffe-style gentleman folders to cut the best.

Here is a look at one:

So Janich and Mike Snody, who we now know for his Spyderco, Benchmade, and KA-BAR collaborations, got together to design Janich’s Wharncliffe idea. Snody was skeptical of the radical design but was soon persuaded after actually making the knife.

Here is my favorite excerpt from the chapter:

After Snody’s underwhelming initial response, I thanked him for his offer and suggested that he abandon the project to move on with his new career. He politely agreed, only to call me back several days later. His first words when I answered were, “You evil _______ [expletive deleted]! I’ve never cut with anything like this before!” It was then I realized that he actually made my design and, more importantly, did some cutting with it.

The result was the Ronin, which had a straight tapering spine toward a piercing point and a straight edge. Spyderco later picked it up for a short time.

After some back and forth and other ventures, Janich most recently came back at Spyderco with Ronin 2 and the Yojimbo 2 — the second iteration of his folding version of the Ronin for Spyderco.

It was better received at that point because people were beginning to understand the merits of Wharncliffe blades on tactical knives thanks to Janich.

And the rest is history.

Nowadays, you can see Wharncliffe blades on knives as diverse as whittlers and last-ditch self-defense fixed blades. It’s been a long road since Lord Wharncliffe had that meeting with his relative in the 1800s.

January 23, 2018 at 9:29 am

Awesome article. Makes me appreciate my Benchmade Snody Gravitator that much more.

November 15, 2018 at 6:48 am

Dear Knife Depot:

Thank you very much for doing this article and for the kind words. I truly appreciate your passion for Wharncliffes and your commitment to both understanding their magic and getting the history right.

You guys ROCK!

Stay safe,

Michael Janich

November 15, 2018 at 10:48 am

Thanks for reading the article, Michael. And of course thanks for all your work with Wharncliffes and the knife community in general!

November 15, 2018 at 8:29 pm

Cool article. Good read, thank you.

February 24, 2019 at 5:09 am

I , have just started carring a Wharcliff blade about 5 yrs ago when I purchased a case sway back jack.

I have bought several case copperlocks with the Wharncliff blades for every day tasks they are perfect now I know the history thanks

August 31, 2020 at 11:55 am

Thanks for nice review on good nife.

December 17, 2020 at 8:13 am

Great info article. Just purchased a Case blue bone wharncliff blade with collectors “certification” . Beautiful knife and your info makes it that more special!

April 8, 2021 at 12:46 am

By doing your own honing, you can likewise control how finely you sharpen the front line. On the off chance that you are cutting famously precarious food sources like exceptionally ready tomatoes, for instance, you may abstain from finely cleaning the edge—going just to the extent a 4000 coarseness stone. Seen under a magnifying lens, such an edge will have more rough pinnacles and valleys to grasp the elusive skin of a tomato. Fundamentally, you are leaving your cutting edge with a bigger number of microserrations to assist with the cutting and give toughness.

December 3, 2022 at 2:54 am

Ahhh, so my Boker Kalashnikov is not a true Wharncliffe. It is a LAMBSFOOT. I do like all the iterations and variations of the Wharncliffe, because I use my EDC MOSTLY to open Amazon boxes. My next Wharncliffe type will be the Auto Kershaw Launch 13. This was a most excellent article giving me the history of my all time fave blade shape. Saving up for my dream knife, the expensive Spyderco AUTONOMY™ G-10 ORANGE. It has a modified Lambsfoot design. Pricey and quite desirable for a professional mariner. Also, I now need to put some sort of Viking SAX knife on my list. I never knew until this article. Well done!

February 15, 2022 at 8:44 pm

Knife Depot totally closed thief customer service department. Nobody answers the phone or returns messages. Nobody responds to emails. Shameful!

April 27, 2022 at 3:19 am

I thoroughly enjoyed that. Thanks. Before the era of the internet, and indeed the era of widespread literacy, stuff was forever being claimed as a first, or new. I suspect most often, genuinely. I was just looking at a ‘calling card’, more like a sheet, in the British museum from Henry Looker, Razor maker. His various goods are pictured, including a folding knife with a ‘Wharncliffe’ blade. It is dated c1780. I’ve no doubt the Wharncliffe story is correct, but the blade shape was likely nothing new. Thanks again.

August 21, 2022 at 7:47 pm

As the article said, there was a similar blade in the 11th century on a Viking Sax sword. The design in the pictures was possibly a copy of that, or just a “light weight” version of a straight razor. As King Solomon wrote “there is nothing new under the sun” and I think that that is pretty much true. If you look hard enough, almost everything has been done before or there is a version of it. It just depends on where you are whether you see the iterations or not.

June 24, 2022 at 8:00 pm

thank you for this wonderful article. I am a woman in her sixties, always having appreciated high quality knives for the kitchen. My son’s B-day is coming up and he is an experienced shooter, very knowledgeable about guns. He also likes knives. I am not very educated about knives + guns. Guns are out of my budget, but I thought a nice pocket knife would make a great gift. After 2 days of browsing, learing and searching, I got hooked. Knives are just so beautiful, besides being wonderful tools. Your article contributed to me getting hooked. I plan on starting my own little collection.

August 21, 2022 at 7:43 pm

That’s cool! I’m in my 20s and I think I’ve had more knives that years of life, but they are so cool to collect and use.

What did you end up getting to start?

December 3, 2022 at 2:58 am

The Wharncliffe blade design and its variations is a perfect utility design for BEST opening boxes, packages, house hold food packages etc. I have found it by far to be the best utility design. You will love the design. HE should as well. It is the ONLY blade design I purchase now.

August 21, 2022 at 7:41 pm

Very cool! I wish they had talked about this in history class. Would have made my life a lot more interesting LOL

So based on this I would say that the Hogue Deka is a lambsfoot design, not a Wharncliffe like most places refer to it as. Is that the case?

August 22, 2022 at 9:25 am

The Hogue Deka is definitely a modified Wharncliffe, which is a catch-all term for knives with many properties of the Wharncliffe, but not exactly like one. If it had a straight edge, it would be a typical Wharncliffe, but that curved belly turns it into a modified Wharnie.

April 20, 2023 at 4:51 am

My Mom was a “Warner”. Grew up on “Warner Hollow Road” above the “Edgemont Reservoir”. Her brothers (my uncles): “Bud”, “Head”, “Pill” & George made knife blades from saws, files, leaf springs and other useful steel that could be forged, ground and heat-treated. Many of their knives were butcher knives and hunters. A couple were “warnies”. My maternal grandmother, “Mom” Warner, used a “warnie” in her kitchen. Great blade for peeling potatoes!

May 30, 2023 at 5:31 am

Great article. Lots of confusion about what is or isn’t a Wharncliffe blade. I just purchased a Kershaw Iredale Stockman. No two retailers seem to agree on the shape of the secondary blade. From this article I’m going to call it a Wharncliffe! It sure isn’t a Sheepsfoot. Great knife by the way.

March 27, 2024 at 1:24 am

Hey Tim,

Thanks for taking the time to research and write this cool article – very interesting! I have a large knife collection, but I do not have any Wharncliffe-shaped blades yet. I must admit, I didn’t really ‘get’ this blade shape’s usefulness and function until after reading your article. I’m going to add the Spyderco Yojimbo and Yojumbo to my wishlist of knives to buy! I think I’ll also look for a cool slip-joint Wharncliffe as well. I really enjoyed your article.

Thanks!